An article published in the Dorset Echo 3rd May 1979 tells of how a French soldier returned to say thank you to a Weymouth family, who offered him shelter, 39 years after Dunkirk.

French officer Fernand Le Bret was overwhelmed by the welcome he received in England after being evacuated from Dunkirk in June 1940. He was particularly grateful to the Wilkins family of Weymouth who put him and fellow officer up for a couple of days and saw them off when they went back to falling France.

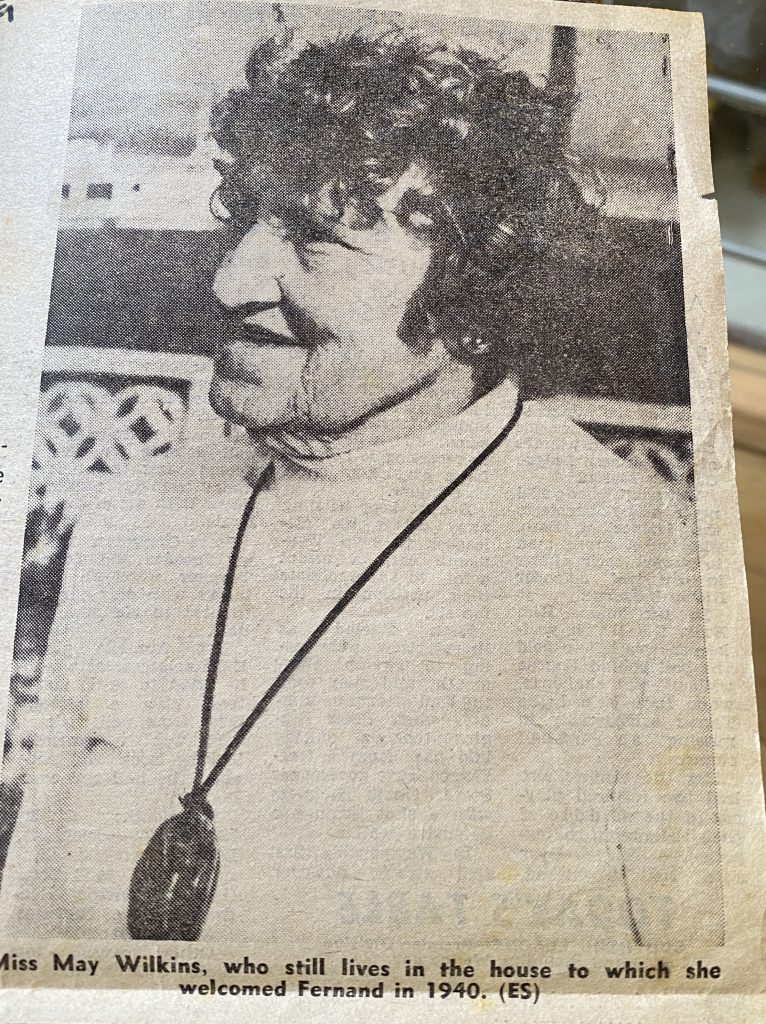

Now after 39 years Mr Le Bret from Franque-Ville St. Pierre near Le Havre has been able to say thank you to 75-year-old Miss May Wilkins who still lives in the house she welcomed him to so long ago.

Miss Wilkins was found at her home in New Close Gardens by Mr Bret’s daughter and son-in-law. Marie-Therese and Jean-Pierre Le-boucher, when they were in England a year ago. The couple who live at Yvetot between Rouen and Le Harve are both English teachers at a French agricultural college and were staying at Dorchester with Mr John Kennedy the vice principle of Dorset College of Agriculture.

Remembering her father’s stories about Weymouth Mrs Le-boucher looked up Wilkins in the phone book and rang Miss Wilkins.

Mr Le-boucher said:

“when we told him last year he was so pleased. He didn’t think we would find her after so many years. He has been talking about it for the past year.”

So they arranged Mr Le Bret’s visit and took Miss Wilkins out to lunch and then opened a bottle of champagne back at her home.

In 1940 Mr Le Bret was one of 2,000 troops who crowded onto a British warship, to be taken off the surrounded Dunkirk beaches. After running the gauntlet of German bombers they arrived at Folkestone and he travelled on, via London and Plymouth to Weymouth. There Miss Wilkins and her sister Mrs Winifred Street went to one of the schools where the soldiers were billeted and invited two to their parents’ home.

Mr Le Boucher who can not speak English said:

“He has always been pro-British since then and is furious sometimes because of the nonsense told in France about Dunkirk and about the British not letting people on their ships.”

Merchant Ship

Mr Le-boucher added:

“He was also impressed with the way the people said ‘welcome’ when they arrived. At all the stations people were there waving and giving them flowers. All the soldiers where picked up by families.”

After staying with Wilkins in 1940, Mr Le- Bret sailed from Weymouth in a merchant ship to Cherbourg. He abandoned his uniform to stop the Germans making him a prisoner of war and travelled to the South of France – which was not occupied until later in the war. He eventually made his way home on stolen bicycles and other strange means of transport.

Meanwhile, the Wilkins came to believe he had been killed – the other officer who stayed with them is dead. Miss Wilkins moved into new close Gardens with her parents Emily and Sidney Wilkins just before the war. Mr Wilkins was killed at the age of 70 when a bomb dropped in the garden next door as he was picking roses.

Mrs Wilkins lived to be 93. Though Miss Wilkins’ brothers and sisters moved out, she still lives in the same house surrounded by the same garden fence to be seen in the pictures she took of the two soldiers in 1940.

Written Letters

Miss Wilkins said:

“When the daughter and her husband came it was a surprise. Since then the father has written letters and she has translated them. He was very excited when he came here and wanted to see the room where he stayed and the room where he sat.”

Mr Le Bret had recalled where they used to keep a piano that Miss Wilkins got rid of last year. He also remembered that when the family saw them off from Weymouth Quay they rolled a newspaper into a microphone to shout to them.

And Miss Wilkins still has the note the two men left which says:

“My friend and me very happy for your reception and your attention.”

It ends:

“Hurrah for England.”

Now she is considering whether to accept an invitation to go to France.

To read more about the Wilkins family please use these links to see their individual family memorials.

Recent Comments